Heroes Of The Taj Hotel: Why They Risked Their Lives

Indian firefighters attempt to put out a fire as smoke billows out of the historic Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai, which was stormed by armed gunmen in November 2008. Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images

Indian firefighters attempt to put out a fire as smoke billows out of the historic Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai, which was stormed by armed gunmen in November 2008.

Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images

On Nov. 26, 2008, terrorists simultaneously attacked about a dozen locations in Mumbai, India, including one of the most iconic buildings in the city, the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel.

For two nights and three days, the Taj was under siege, held by men with automatic weapons who took some people hostage, killed others and set fire to the famous dome of the hotel.

The siege of the Taj quickly became an international story. Lots of people covered it, including CNN’s Fareed Zakaria, who grew up in Mumbai. In a report that aired the day after the attacks, Zakaria spoke eloquently about the horror of what had happened in Mumbai, and then pointed to a silver lining: the behavior of the employees at the Taj.

Apparently, something extraordinary had happened during the siege. According to hotel managers, none of the Taj employees had fled the scene to protect themselves during the attack: They all stayed at the hotel to help the guests.

«I was told many stories of Taj hotel employees who made sure that every guest they could find was safely ferreted out of the hotel, at grave risk to their own lives,» Zakaria said on his program.

There was the story of the kitchen employees who formed a human shield to assist guests who were evacuating, and lost their lives as a result. Of the telephone operators who, after being evacuated, chose to return to the hotel so they could call guests and tell them what to do. Of Karambir Singh Kang, the general manager of the Taj, who worked to save people even after his wife and two sons, who lived on the sixth floor of the hotel, died in the fire set by the terrorists.

Often during a crisis, a single hero or small group of heroes who take action and risk their lives will emerge. But what happened at the Taj was much broader.

During the crisis, dozens of workers — waiters and busboys, and room cleaners who knew back exits and paths through the hotel — chose to stay in a building under siege until their customers were safe. They were the very model of ethical, selfless behavior.

What could possibly explain it?

Getting To The Bottom Of It

Earlier this month, a study in the Harvard Business Review proposed an answer to that question.

The study was done by Rohit Deshpande, a Harvard business professor who researches both business ethics and global branding.

About nine months after the attacks on the Taj, Deshpande was in India interviewing senior management of the hotel on a completely different topic, but found that the people he was talking to kept steering the conversation back to the terrorist attacks.

«What was interesting about all those interviews with senior management was that they could not explain the behavior of their own employees,» he told me. «They simply couldn’t explain it.»

An NDTV tribute video to the brave staff of the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel.

YouTube

And so Deshpande decided to do his own investigation of the company to see if he might be able to untangle the cause.

Last year, Deshpande flew to India to review the company’s HR policies and also do interviews with the hotel staff, everyone from managers to kitchen workers.

What he published in the Harvard Business Review is his case study of the company.

Now, because this is a case study and not a double-blind research study, it’s impossible to draw definitive conclusions. But this is what Deshpande thinks:

«It perhaps has something to do with the kinds of people that they recruit to become employees at the Taj, and then the manner that they train them and reward them,» he says.

From A To Z — Recruitment To Reward

First, recruitment. In their search to find maids and bellhops, the Taj avoids big cities and instead turns to small towns and semi-urban areas. There the Taj develops relationships with local schools, asking the leaders of those schools to hand-select people who have the qualifications they want.

«They don’t look for students who have the highest grades. They’re actually recruiting for personal characteristics,» Deshpande says, «most specifically, respect and empathy.»

Taj managers explained to Deshpande that they recruited for traits like empathy because that kind of underlying value is hard to teach. This, he says, is also why recruiters avoid hiring managers for the hotel from the top business schools in India. They deliberately go to second-tier business schools, on the theory that the people there will be less motivated by money.

And this strategy, as Deshpande points out, is highly unusual in India.

«Let me put this into a little cultural context for you,» he says.

«India is a country where people are almost obsessed about grades. In order to get ahead, you have to have really high grades. But here is an organization that is doing just the opposite — they’re recruiting not for grades, they’re recruiting for character.»

Part of this focus on character is ideological, he says.

The Taj is owned by a corporation called the Tata group, which for the past hundred years has been run by an extremely religious family that’s interested in social justice: The company typically channels about two-thirds of its profits into a charitable trust.

But Deshpande says there are also practical reasons for this focus on character. The Taj hotel has made its name on customer service, and they are near maniacal about it, treating it almost like a science.

For example, managers have mapped the number of interactions that happen between customers and hotel employees in a typical 24-hour stay. There are on average 42, often unsupervised, interactions between employees and guests.

Each of these interactions is viewed by the company as an opportunity for employees to delight their customers with their kindness. So everything — everything — about the training and rewards systems set up by the Taj is designed to encourage kindness.

Deshpande gives one example. «If guests say something or write something very complimentary about an employee, within 48 hours of [the] recording of that compliment, there is some sort of reward that is made.»

Rewards range from gifts to job promotions.

This system — of immediately rewarding desired behavior — will likely sound familiar to people interested in psychology.

It’s by-the-book conditioning, the same kind of conditioning used by B.F. Skinner to train his pigeons.

And in his study, Deshpande argues that it is this combination of selection and routinized rewards that explains what happened during those terrible three days when the Taj hotel was under siege.

The employees, he argues, were essentially performing the behaviors they were selected and trained to perform. In this case, extreme kindness to customers.

Enabling Ethics

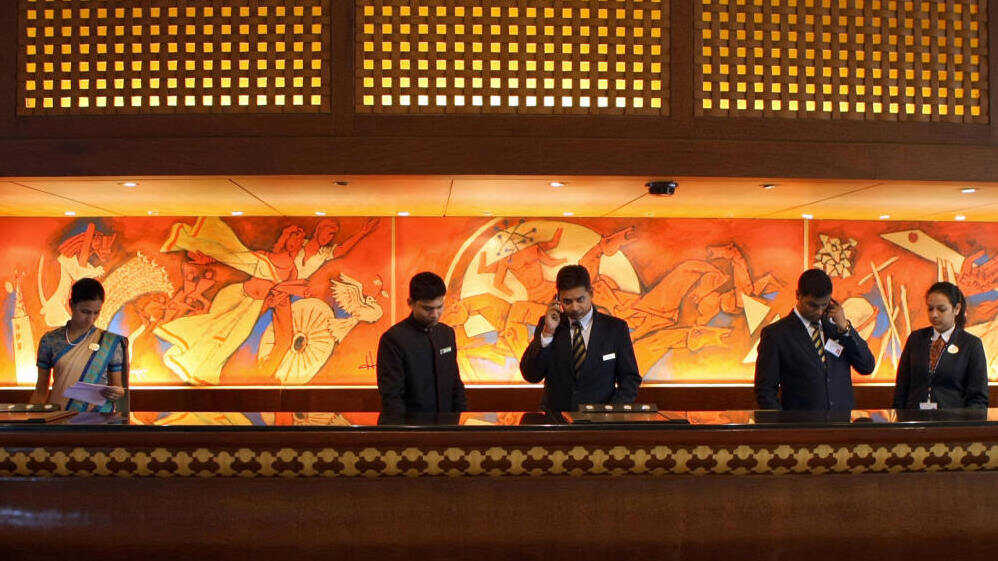

The reception area of the Taj Mahal Hotel reopened on Dec. 22, 2008, less than a month after devastating attacks that rocked India’s financial and entertainment capital. Sajjad Hussain/AFP/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Sajjad Hussain/AFP/Getty Images

The reception area of the Taj Mahal Hotel reopened on Dec. 22, 2008, less than a month after devastating attacks that rocked India’s financial and entertainment capital.

Sajjad Hussain/AFP/Getty Images

And for Deshpande, all of this has much larger implications: For him, what happened at the Taj is proof positive that organizations can create ethical behavior.

«I am absolutely convinced that corporations can enable ethical behavior, and I think what happened at the Taj on [Nov. 26, 2008] is a great example,» he says.

But Tom Donaldson, professor of business ethics at the Wharton School, says producing ethics isn’t so simple.

«If ethics could be engineered by the organization infallibly, we wouldn’t be hearing about so many scandals in church organizations,» he says.

It’s not that rewards don’t matter, Donaldson argues. They profoundly influence behavior, he says. But Donaldson wonders if all the training and conditioning done by the Taj can really be said to have produced truly ethical behavior. What would happen, he wonders, if those employees had confronted a different kind of ethical dilemma, one presented by the customers they’d been conditioned to serve?

«I’d like to know what a Taj employee would do,» he says, «for example, if one of the guests ended up striking a homeless person, or one of the guests attempted to sexually assault a hotel worker.»

It’s hard to condition real ethics, he says.

But for Deshpande, in the example of the Taj and the incredible sacrifices of the employees who work there, there is still a clear, and very compelling, lesson.

«Corporate design is absolutely critical,» Deshpande says. «For good, and for evil.»

Читайте далее: